Once upon a time, when Cooper was a little puppy, we took him for a walk in the wild where the boy met another cocker spaniel. And as all pup parents we stop and chatted about the way our pups are raised, groomed and fed. At one point the other pup’s dad mentioned that he swears by natural treats…. freshly shot pigeons, rabbit ears covered in fur, raw bones, dried chicken legs… the list went on. At the time I never heard of those.

I did a bit of googling upon return, found a few things, but never felt convinced enough to give them to my puppy.

A few years on, and there is a huge array of treats available around to keep the dogs happy.

But are they actually safe?

The first thing you need to bear in mind is that very few of those treats would be suitable for a cocker spaniel puppy. The only exception is sweet potato but even those need to be looked at with caution because, as it happened last year, they can arrive covered in mould due to poor manufacturing or storage.

Any dehydrated body parts may suit an adult dog with a robust digestive system, but they contain too much protein (pigs ears, for example, contain 73%) for a little puppy and thus can increase the risk digestive upsets as well as skeletal problems in the future.

Additionally, not every company can guarantee complete product safety, so the chews and treats may be contaminated with bacteria, toxins (as a by-product of bacteria lifecycle or from the animal source), pathogens or chemical residue (unless you can absolutely guarantee that the animal has never been treated with antibiotics or fed a pesticide-free diet, just to give you an idea)

For example, when a study published in Canadian Veterinary Journal examined 26 random bully sticks, all 26 were found to be contaminated with bacteria including Clostridium difficile, MRSA, and E. coli. It followed the 2019 case when FDA issues a recall for all pig ear treats due to salmonella outbreak.

An adult dog may show no symptoms and have no side-effects, but the puppy’s gut defences are still weak and can be affected.

There is also a possibility that the asymptomatic dog will shed salmonella for about 7 days, potentially passing it onto his human family.

Some animal body parts can contain high levels of specific minerals and vitamins, which can potentially cause vitamin and mineral imbalance in the dog’s body.

Others, like pig ears, are naturally high in fat and can lead to weight gain, diarrhoea and even increased risk of pancreatitis.

Certain body organs can naturally contain hormones. If a dog regularly consumes such treats, his own endocrine system can be affected.

Treats add calories. It is known that a typical 20cm raw hide chew can contain as much as 100 calories, which is roughly 15-20% of your dog’s daily requirement. Considering that all treats should fall below 10%, anything on top can lead to weight gain and obesity. Reducing the amount of food your dog eats for a sake of giving him a chew can create a deficit or excess of major nutrients and cause problems.

Not every chew is safe. Some can splinter, others can cause blockages or perforations of the gut.

Antlers, hoves, horns and bones may be extremely popular among dogs, but they are also a major concern among vets because these can cause jaw dislocation and broken teeth, especially in dogs who really do love to chew hard.

Fish skins are suitable for most dogs, but not puppies under 4 months of age.

Liver treats appeal to all dogs, but they are incredibly rich in vitamin A and can cause toxicity if used frequently or generously. Liver is also a detoxifying organ, so any residue from those toxins can end up in your dog’s body.

Dehydrated meats often referred to as jerky can cause Fanconi syndrome. The illness causes kidney damage, can become chronic and even be potentially life-threatening. The symptoms of Faconi syndrome are not easy to spot and usually include changes in urination and drinking habits and can mimic the ones of diabetes, kidney disease and urinary tract infection. It is impossible to say which treats may lead to problems – so far it has been established that the issue does not relate to a particular manufacturer or a country of origin, but has to do with a certain substance in the treats. And the substance is yet to be identified.

So what can you do if you want to treat your dog safely?

Choose a trusted UK-based (or EU-based) company that follows strict guidelines for product safety, happy to provide you with additional details and inform of any food recalls should the worst happen.

All reputable UK pet food companies should be registered with PFMA

All UK companies that produce any treats made from by-products must be approved by APHA. Depending on their set-up, they are often required to obtain a licence from a local authority, too.

Any pet food manufacturer should have at least one nutritionist who holds a veterinary degree and/or is trained in small animal clinical nutrition.

Check the packaging label for any age restriction. If you can’t find any, contact the company.

Always check the treats for signs of mould and odd smells (even though some can be a little smelly, but they should not stink)

Give these chews once a week at most, not on a daily basis.

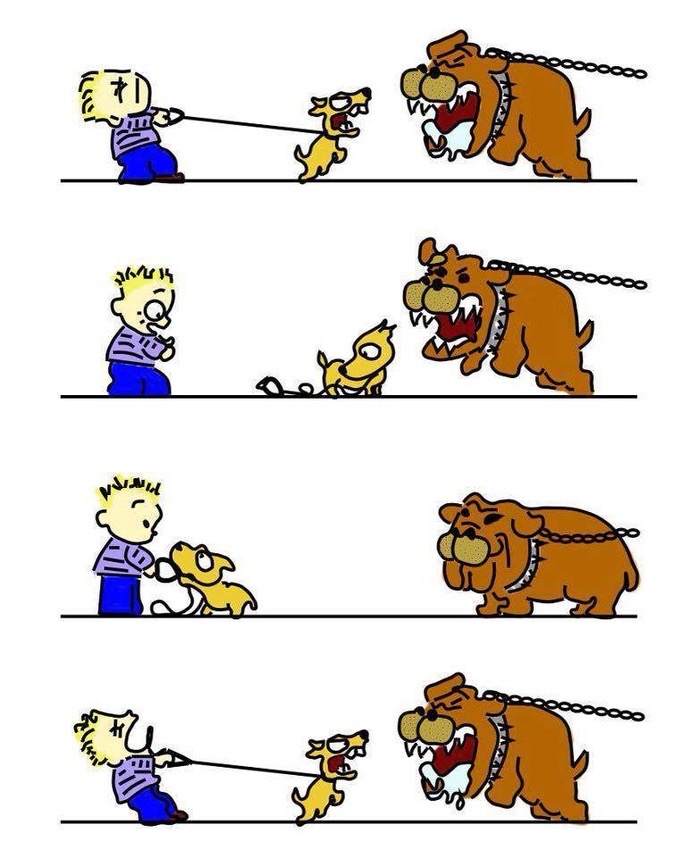

Always supervise your dog when he is busy chewing.

If in doubt, bin – don’t feed.

Make your own treats or indulge your dog’s need to chew by giving him crunchy slices of carrots and apples.

If your dog has diagnosed health conditions, is genetically predisposed to such illnesses as pancreatitis, or requires a special diet, always consult your vet before you use these (or any) treats.

Photo credit: image by Mikhail Dmitriev for 123rf.com